The High Costs of Hiring and Turnover

Hiring the right person for the job is a challenging assignment. It’s not only difficult to do; it is costly when we miss. It is expensive in terms of turnover costs, and it is expensive in terms of poor productivity.

The Department of Labor estimates that it costs ten to twenty times a person’s weekly wage to turn them over -and that is for entry-level people. For qualified to journey-level employees, it is considerably more expensive than that. In addition to the simple replacement costs of recruiting, advertising, interviewing, and other onboarding costs, one has to consider lost opportunities, angry customers, and so on. It’s a considerable number, and if it were a line item on anyone’s budget, people would pay much more attention to it.

As costly as turnover is, sub-standard or poor job performance among your existing employees is equally devastating in terms of cost. There are considerable differences in job performance among your employees; as you know, those differences are all bottom-line considerations.

The differences are more significant than you think. If you ask one of your supervisors who oversees about 20 people to name their “best” and “worst” employees in a given job category, they will have no problem doing it. Then, ask them how much more productive their “best” performer is than their “worst.” They will tell you and incorrectly tell you differences of 10 to 15%. You can get them as high as 30% if you push them hard. Rarely will they go over 30%. Thirty percent sounds like a lot to them, and it is. If you increase productivity 30% (or even 10%, for that matter), you’d be putting big dollars to the bottom line.

Controlled experimentation, however, has shown that those estimates are conservative. For instance, in one study, a group of clerical people were observed counting the number of pieces of paper they got filed in a day. This study revealed that the “best” clerks were two and three times more productive than their “barely acceptable” counterparts. These differences equate to significant differences in performance and productivity outcomes on the job.

Reflect on your careers, the people you have worked with, and those who have worked for you. You have certainly seen ranges in performance that are greater, much greater than 30%. Perhaps you were blessed with a “best” type of Administrative Assistant. They leave for some reason or another, and now you need two people to do what they were doing. Have you ever been served by a “best” waitress and a “barely acceptable” waitress? How big a difference was there? Those are the differences Scheig’s methodology distinguishes and what you can verify from your work history and experience.

Can you imagine the differences in productivity with a whole crew of the “best” employees? What does 300% less re-work do for your bottom line?

The Crucial Role of Selection

While there are multiple factors related to the problems of turnover and performance, both issues share a common beginning: selection. Performance begins with selection. The pain of identifying and hiring the “best” candidate is more acute in industries with a shortage of qualified labor to fill the position. The motor coach industry is a prime example. Saddled with regulations and a short supply of drivers who qualify has forced the industry to hire those who are minimally qualified, that is, those who meet the basic requirements. A “best” driver becomes whoever meets the minimum qualifications in terms of all the state and Federal requirements. Some companies can almost not afford to turn away such a “qualified” driver. After all, they have ten empty buses in the yard and aren’t making any money sitting there. Situations like this put tremendous pressure on recruiters to get the positions filled. It isn’t as if recruiters wouldn’t like to be more selective, but in an industry governed by regulation and shortage, in many cases, they feel they have no choice.

Although it is sometimes made to sound that way, companies are not hiring everyone who walks in the door with a CDL and other requirements. The industry has significant turnover, so much hiring is happening. The question is, are they hiring the right drivers? The variance in performance spoken about earlier also applies to ” qualified ” people based on regulations. Ten “qualified” drivers will vary in their performance. The trick is identifying and hiring those most likely to perform like your “best.”

There are two solutions for an industry that is plagued by worker shortage and emphasis on qualifications regulated by the government:

Do a better job of screening applicants who meet the mandated minimum qualifications to identify drivers like your “best.”

Identify and train new people to enter the industry. Both are selection issues and in the second case, it is not good enough to think that anyone who shows interest can be trained to be among the “best” or even complete the training.

The Importance of Training Beyond Technical Skills

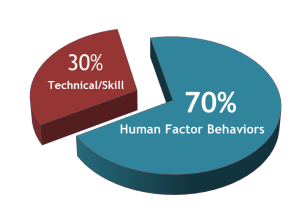

With good reason, most training efforts focus on the skill part of the job. But skills typically represent only about 30% of any given job category. 70-80% of the job involves human factor behaviors, which also significantly impact overall job performance. One cannot predict total job performance based on thirty percent of the job, and this is the crux where those hiring motor coach drivers and diesel technicians find themselves.

Please understand skills are essential to the job but are best viewed as minimum qualifications. One cannot become a Motorcoach driver without a CDL (a minimum skill indicator for drivers). Neither can one become a journey-level diesel technician without knowledge and hands-on experience. What about the other 70-80% of the job recognized as things that distinguish top performers from their barely acceptable counterparts?” No one would expect to hire the entire graduating class of some driving school or technical college and not experience variance in actual job performance. All are “qualified” yet actual job performance can and will be all over the place. The reason is the other seventy percent of the human factor behaviors that make up the job.

We have great faith in the training function in America. American companies spend millions of dollars every year on training. There has been an attitude that we can train almost anyone to do anything, and we have developed very effective training techniques. Again, most training focuses on the job’s hard skills or technical parts. But if training only impacts 30% of the job, it is a small wonder that we continue to find such variance in overall job performance.

The “soft” skills or human factor behaviors that a specific job requires are challenging to train for and, short of some heavy behavior modification programs, almost impossible to achieve. That is why it is common to hear that one should hire for the behaviors and train for the skills in the selection process. Training efforts are much more successful if the trainees already possess the critical human factors necessary to be among the “best” when taught the technical.

Companies spend time, talent, and lots of dollars every year trying to train people to be something they are not and never will be. Sure, they will learn the technical, but will they be good at the job? If you are a trainer, how often have you asked yourself as you meet your new training class, “How do they expect me to make silk purses out of sow’s ears? Please give me something that I can work with.”

Whether for selection for employment or selection for entrance into training programs, being able to assess the candidate against a success profile for the job is critical.

Creating Success Profiles for Effective Selection

Success profiles necessarily incorporate skill sets but also those other 70% of non-technical behaviors (some call these soft skills). Too often, companies need to learn what they are looking for beyond some level of technical competence, e.g., beyond a CDL or a particular score on a skills-knowledge test or graduation from a technical program. Their focus has been on skills or credentials with little or no way to look at the other behaviors that distinguish superior performers from the rest of the minimally qualified. They need a complete job success profile to measure the applicant against systematically. At best, they are working off some job description. A job description describes what all or most of the job incumbents do. Still, it does not identify which job behaviors distinguish between top performers and the rest of the pack, which job behaviors, if absent, cause trouble on the job, and which job behaviors account for the most variance in performance outcomes.

Management can sometimes be surprised by how their “best” performers do the job efficiently and effectively. Some of the job behaviors management believes are essential for success in the position may be considered less important, sometimes far less important, by those considered to be among the “best.” The only way to get this kind of information is to sit down with their “best” performers and find out from them how they actually do their job and how they do it so well.

A job success profile is essential for selection from those who are minimally qualified or certified. It is also crucial for selection into training programs that mainly emphasize hard-skill behaviors. It is indeed possible to teach people the technical, but it is almost impossible to teach them the other behaviors required for success on the job. Hiring for the behaviors and training for the skills is much easier.

The Pitfalls of Relying on Interviews Alone

Interviewing becomes almost useless without a success profile of the whole job (not just the technical). It is little wonder that all of the literature suggests that the average interview is, at best, a 50/50 proposition (often, it is less than that since we frequently find ourselves trying to choose between two people, neither of whom is very good). The interview doesn’t need to take place; flip a coin, and the accuracy is the same.

The odds go up in the hands of people with some training and experience, but without a job success profile, it is still very subjective. A whole industry has grown up around teaching people how to pass interviews. The hiring authority doesn’t know whether they are dealing with the “real” or “trained” person. Additionally, interviewing behavior is different from job behavior, and while some people interview well, their job performance is less than stellar and visa-versa. The more obtuse the interview questions become to combat the seminar-trained applicant, the farther away they get from the applicants’ ability to do the job and do it well.

Maximizing Employee Potential Through Pre-Employment Assessments and Training

Companies spend millions of dollars yearly trying to train people to be something they are not and never will be. If you are a trainer, how often have you looked at your new training class and asked yourself, “How do they expect me to make silk purses out of sows’ ears?” Just because someone can be taught the technical does not mean they will be among the “best” when their training is completed. Only some people who are interested in training are worth the effort.

Remember, whether selection for employment or selection for training programs, hire for the behaviors, train for the skills. The behaviors used to select candidates should reflect a job success profile that includes the job as a whole and not just the technical.